Credit: Lauren Miller, Montana Free Press, CatchLight Local/Report for America

Editor’s note: This story contains descriptions of suicide, depression and grief. If you or someone you know is struggling with mental health, the 988 hotlineis available 24/7 by phone, text message, online chat or video phone.

BLACKFEET RESERVATION — The air was getting colder, winds were picking up, the barn windows needed sealing, and Lynn Mad Plume was at a breaking point.

Her brother Wyatt had taken his own life less than two years before at age 29.

For about a year, Lynn and her younger sister, Erika Mad Plume, had been trying to turn their grief into something concrete and purposeful. Specifically, they wanted to provide free mental health resources to community members in the company of horses, animals their brother had loved. Local men in particular, Lynn and Erika said, tend to resist talk therapy. And many were grappling with compounded grief like their brother. Between age 11 to 29, Wyatt lost eight close family members or friends, including five to suicide, murder or addiction.

They hoped an alternative, informed by a blend of emerging mental health research and longstanding cultural traditions, might help reduce the likelihood of a death like their brother’s. They were eager to make a dent in daunting statistics that no one had figured out how to crack.

Montana has one of the highest suicide mortality rates in the country, and the crisis is particularly severe in tribal communities. From 2005 to 2014, Native Americans in Montana had the highest suicide rate compared to other demographics, and Native youth, ages 11 to 24, had a suicide rate almost three times higher than that of their white peers.

On the Blackfeet Reservation, nestled beneath the Rocky Mountain Front in northwest Montana, residents say suicide can seem ubiquitous. A 2017 survey of 479 reservation residents — some of the most recent publicly available data — found that one in three adults surveyed said they felt depressed or sad most days, a risk factor for suicide. More than 40% of eighth-graders at Browning Middle School, about 14 miles north of the Mad Plume sisters’ home on the reservation, reported having suicidal thoughts, and one in three said they had attempted suicide, according to the same 2017 community survey. Lynn and Erika’s goal was to keep their community’s children alive.

But by October, money had been tight for months, and it was running out. The horses needed hay for winter, and for the first time, Lynn started to consider walking away. On days when the pressure felt particularly hard to bear, she would stroll outside her home in Two Medicine, spend time with the horses and think of Wyatt.

“This has to work,” she’d think to herself. But then another thought would creep in, and she’d wonder if the venture was financially feasible.

The sisters have seemingly ideal credentials to create a mental health program that incorporates horses. Erika, 26, is a licensed social work and addiction counselor candidate who is earning her equine-assisted mental health practitioner certificate, and Lynn, 32, has a Ph.D. in Indigenous health, a master’s degree in public health, and oversees a substance use disorder treatment program that incorporates horses through Johns Hopkins Center for Indigenous Health.

But the abandoned barn they hoped to fix up before winter introduced more mundane challenges. They needed to remove the piles of manure inside. They needed to wire the structure for electricity and buy portable heaters.

“I was going to give up on everything,” Lynn told Montana Free Press in early November. “I was done. I didn’t want to do this anymore.”

If she had given up, she would have been part of a longstanding trend. Suicide prevention programs have cycled through the Blackfeet Reservation community for decades, rarely lasting longer than a few years, according to tribal health leaders. In fact, the old barn the Mad Plumes are renovating in Browning, the seat of tribal government, had been abandoned more than 10 years earlier when a different youth mental health program housed there was shuttered.

But one morning in late October, Lynn got an email saying they’d received a $50,000 grant from the Social Justice Fund NW, a foundation that supports grassroots efforts in Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington and Wyoming. The money, Lynn said, would help buy winter hay for the horses and “keep our doors open.”

“OK,” she thought. “We can keep going.”

HELPING WITH HORSES

“Hello!” The child’s voice fills the barn with excitement.

“Oh hey, Lizzy!” Lynn calls. “I’m over here.”

A little girl in a pink sweatshirt bounds toward her, arms open for a hug.

Ten-year-old Elizabeth “Lizzy” Steward tries to come work with the horses at least once a week. She attended Lynn and Erika’s first community event — an Easter egg hunt with horses in Heart Butte — and when Lynn saw how much Lizzy loved the horses, she invited her and her siblings to participate in the program at the Mad Plume’s family property in Two Medicine, about 14 miles southeast of Browning. (They hope the barn they’re fixing up will eventually make their services more accessible to reservation residents who live, work and attend school in Browning.)

Outside the barn, Lynn’s father, Nugget Mad Plume, hoists Lizzy atop a 22-year-old brown mare. Lizzy rests her head on the horse’s neck and lets out a deep sigh, then sits up and braids its mane as Lynn leads her around the corral.

Lizzy is one of around 35 kids, ages 6 to 14 who have participated in a version of this program since April. Through their family nonprofit Two Powers Land Collective, Lynn and Erika provide clinical counseling with horse interaction, therapeutic riding and equine-assisted learning for adults and children on the reservation. Some attend individual sessions, others attend group lessons or occasional camps. All programs are free.

Erika is in the process of completing her certificate in equine- assisted mental health through an online program at the University of Denver, but she does not technically need it. Clinical counseling that incorporates horses is largely unregulated in the U.S., simply requiring practitioners to have some kind of mental health license. In addition to the Social Justice Fund NW grant, in the last two months, Lynn and Erika received two additional grants, from the American Psychiatric Association and the Montana Community Foundation. They’ve also partnered with Sukapi Lodge Mental Health Center, a new youth substance-use treatment facility on the reservation, to reach more people.

Some kids are dealing with grief or learning disabilities and others just like being around horses. Few are actively suicidal. But the hope, the sisters say, is that by starting young and helping children regulate and process their emotions, they will improve their overall mental health. And on the Blackfeet Reservation, where there aren’t many structured activities for young people other than sports, the Mad Plumes are hopeful that their programs will provide kids a sense of purpose and belonging.

A few months earlier, during a summer session, Lynn and Erika had taught participating kids how the Blackfeet people historically painted their horses. The lesson, Lynn said, was designed to encourage kids to connect with their culture and talk about their feelings. Lizzy created a handprint, the symbol for the Missing and Murdered Indigenous People movement, in honor of her uncle, who had died. She told the group what the symbol meant to her and what happened to her uncle.

“A lot of kids don’t like to talk about their feelings,” says Lizzy’s mom, Justine Steward. “They just bottle it down. But when they’re on a horse, it does a lot.”

A growing body of research shows that interaction with horses adds benefits to psychotherapy, enhancing patients’ psychological, social and emotional outlook. Nina Ekholm Fry, faculty member and equine programs director at the University of Denver’s Institute for Human-Animal Connection, said interacting with animals in the outdoors extends the benefits of psychotherapy to people who may be underserved by traditional therapeutic settings.

“This whole idea of just sitting down and talking back and forth isn’t for everyone,” Ekholm Fry said. “It’s actually quite limiting in some ways.”

When it comes to suicide prevention specifically, research on the effectiveness of services that include animals varies. One 2021 study found that education, therapy and activities that incorporate animals maximized the benefits of therapy and increased children’s motivation to follow through with treatment plans. Participants showed reduced suicidal ideation and self-harm and were “more positive with regard to seeking help for their suicidal behavior.” Animals, which can provide unconditional love and show affection, are, according to the report, “uniquely suited to interventions with children and adolescents who have suffered traumatic experiences.”

“They encourage spontaneous communication, motivate patients to engage with the therapeutic process and reduce the feelings of rejection and stigmatization, which are all key elements of a successful intervention process,” the study says. A recent European Journal of Psychiatry report that reviewed 11 animal-assisted therapy articles found that while the practice is associated with a number of protective factors against suicide — like improved emotional regulation and increased help-seeking behaviors — “a considerable number of studies with non-significant findings” means that “conclusions cannot be drawn regarding animal-assisted therapy’s efficacy in suicide prevention.” It also noted some drawbacks to the practice, including the difficulty of training animals and the addition of financial burden.

The Mad Plumes are also hopeful that by tapping into Blackfeet culture they can help young people survive the traumas of historical and contemporary life and thrive. Another area of research has found that community members’ connections with Native languages and cultures bolster a healthy sense of identity and self-esteem, improve health outcomes and strengthen social resilience within Indigenous populations — all of which are known to lessen suicide risk.

Lynn said getting people to participate has been the easiest part. As soon as she put the word out on the Two Powers Land Collective Facebook page, kids started showing up.

Lynn wishes Wyatt could have participated in a program like this.

“Wyatt didn’t want to go sit in a room and talk to somebody that he didn’t know,” she said. “But we’ll get Wyatt’s friends, and our cousins, that feel the same way. They’ll go be with the horses. And it’s just much easier for them to do that there.”

‘HE NEVER LET YOU KNOW THAT IT WAS HARD ON HIM’

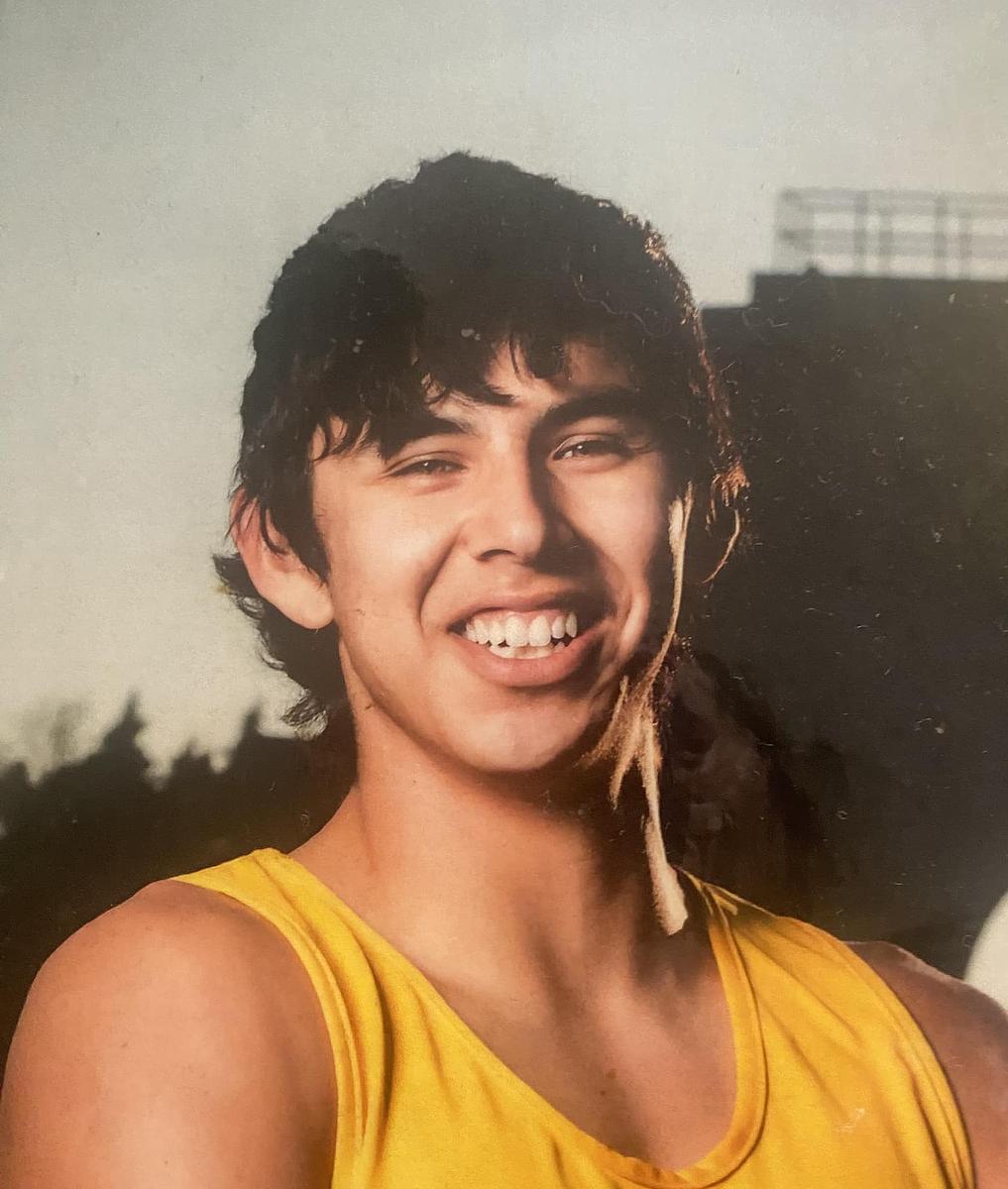

The Wyatt Mad Plume his family remembers was a fierce athlete and perpetual jokester who cared deeply for others.

His sisters say they’ll never forget his first race, a fun run in Bozeman where Wyatt, then in elementary school, outran people much older and taller than him.

“He was so fast,” Lynn recalled.

By the time he started Browning High School, Wyatt had become a serious runner. In his senior year, his family said, he was the only track and field athlete from the reservation to travel to the state championship in Laurel, where he took fifth place in the 1,600-meter dash. He went on to run at Haskell Indian Nations University in Kansas, where he earned an associate degree in liberal arts.

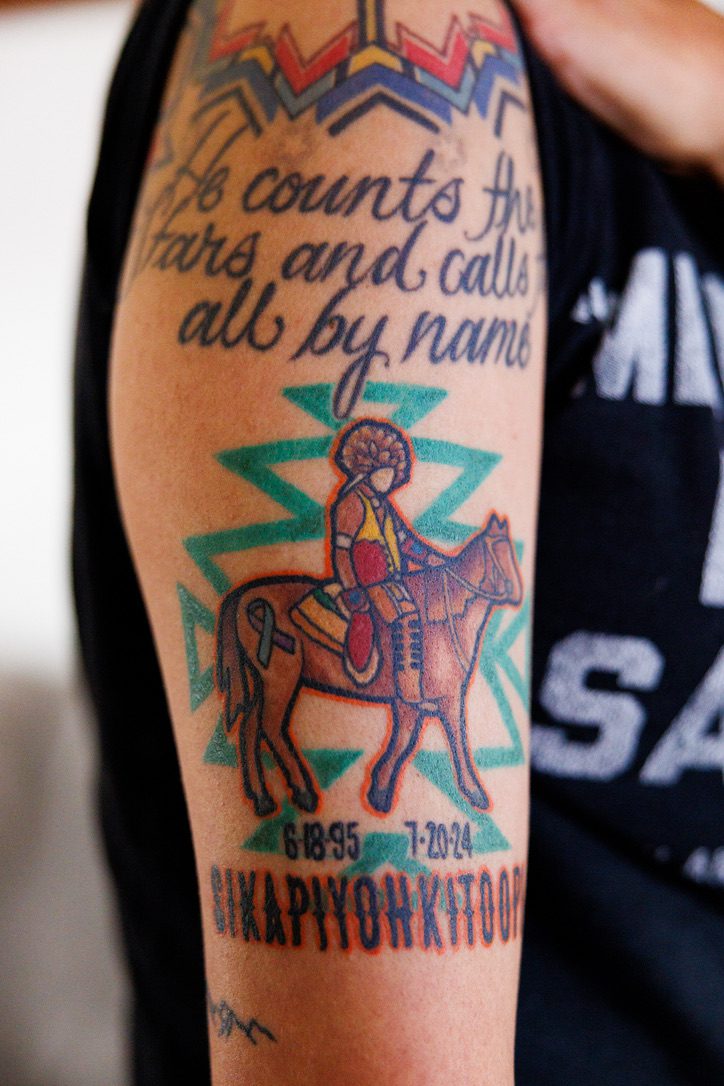

Wyatt always loved horses. He helped break colts with his father, and he started participating in rodeo when he was 3 years old. After graduating from Haskell, Wyatt excelled at saddle bronc riding and competed at the 2017 Indian National Finals Rodeo in Las Vegas.

The second-oldest sibling after Lynn, Wyatt doted on his four sisters. At Haskell, he used scholarship money to buy Erika a prom dress. When Lynn moved to North Dakota for graduate school, he helped pay the deposit on her apartment. Wyatt’s younger brother, Thunder, wanted to be just like him. Family and friends say Wyatt loved most of all to make people laugh. He joked with strangers on the street and at basketball games. He gave nicknames to acquaintances and shared elaborate handshakes.

“He was one of those people that you just want to be around,” said Isaiah Crawford, Wyatt’s childhood friend.

But grief was never far from Wyatt. On his eleventh birthday, his 25-year-old uncle Cricket was murdered. A year later, his 67-year-old grandfather William died of cancer. His great-grandmother Mary, who helped raise him, died the year Wyatt graduated high school. After Wyatt graduated from Haskell, his 21-year-old cousin died of an accidental drug overdose. Just over a week later, his grandmother Penny, who had also helped raise him, died at 66. In 2020, when Wyatt was 25, a close friend just a year younger died by suicide.

A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that Native Americans lose family members “too soon” and “too much” compared to other racial or ethnic groups. And further research shows that experiencing the loss of a loved one, especially when the death is due to violence or suicide, has far-reaching health consequences, including increased feelings of depression.

Wyatt’s mother, Diana Burd, could tell her son was struggling in 2020. He’d been drinking more than usual, and Wyatt wasn’t himself when he was drinking. He was distant, harder to talk to. He didn’t joke.

Determined to help, Diana began taking Wyatt to Blackfeet Community Hospital, the Indian Health Service facility in Browning, for emergency care. It was a complicated journey.

Over the course of four years and dozens of visits, doctors diagnosed Wyatt with alcohol use disorder and depression, among other conditions, according to medical records his family shared with Montana Free Press. Wyatt was prescribed medications to treat depression and anxiety and help him sleep. He was given intravenous vitamins and took surveys screening for depression. Providers talked with him about safety plans. Between 2020 and 2024, Wyatt saw more than 30 different Indian Health Service providers. Sometimes the hospital referred him elsewhere, like an addiction treatment center in Kalispell, for more specialized care. Indian Health Service officials declined to comment on the specifics of his care.

Wyatt’s struggles became so challenging that Diana started carrying a black briefcase filled with his medical records. She’d show his history to doctors, nurses, tribal court officials and anyone else who would listen, hoping they’d recognize her son needed serious help. She felt Wyatt might need to be involuntarily committed for mental health or substance use treatment, and even began hoping he would be arrested and ordered by tribal court to participate in some kind of healing program.

Some members of Wyatt’s family believe the quality of care he received was a factor in his death. In November, six months after MTFP began reporting this story, his parents filed a lawsuit against the United States alleging that Indian Health Service providers “were negligent and violated the standard of care in failing to properly assess and timely refer Wyatt Mad Plume to other medical care providers.” An IHS spokesperson declined to comment on pending litigation, but said “we remain committed to addressing the unique factors that contribute to suicide overall among American Indian and Alaska Native communities.”

Over the years, Lynn watched Wyatt work hard to get healthy. He went to the gym. He wrote his goals in notebooks. Sometimes he went days or weeks without drinking. But each new death set him back. In the two months after his 24-year-old friend’s death by suicide in 2020, Wyatt made three suicide attempts, according to his medical records.

On Mother’s Day in 2022, he introduced his mother to his new girlfriend. For a while, Diana said, he seemed hopeful. They talked about getting married and having children. But in the fall of 2023, Wyatt’s 33-year-old girlfriend died from drug-related complications. Diana said Wyatt was with her when she died. She told doctors that Wyatt was drinking more and “hasn’t been the same since.” Two months after his girlfriend’s death, he’d made four more suicide attempts.

“He was there, but he was gone,” Wyatt’s father, Nugget Mad Plume, told MTFP. “He wasn’t my boy.”

In the winter of 2024, Wyatt received treatment at the Montana Chemical Dependency Center, an inpatient addiction treatment center in Butte, where he worked with a counselor to process his grief.

“He seems to feel as though he burdens others with any emotions that are not based in happiness,” a counselor wrote in Wyatt’s discharge papers. “Bottling his emotions has led to suicidal ideation.”

A month after he returned home from treatment in Butte, Wyatt’s best friend, who’d supported him through his girlfriend’s death, died of an accidental drug and alcohol overdose at age 25. Diana remembers the moment a mutual friend called with the news and Wyatt left the house to drink with friends.

“That’s what the kids do here, is they drink,” she said. “When something like that happens, it’s ‘Let’s go drinking.’”

In July 2024, four months after his friend’s death, as Wyatt was preparing to enter an alcohol treatment program, he took his own life while staying at a relative’s house in Great Falls. He was 29 years old.

In the months following Wyatt’s death, Diana felt suicidal herself. For the first time, she said, she felt she could understand the depths of his pain.

ONGOING AND ACCUMULATING TRAUMAS

Why are suicide rates so high among Native Americans in Montana? Tribal health experts say there’s no simple answer.

One theory is that suicide in Indian Country cannot be separated from historical, ongoing and accumulating traumas related to colonization.

Credit: Lauren Miller, Montana Free Press, CatchLight Local/Report for America

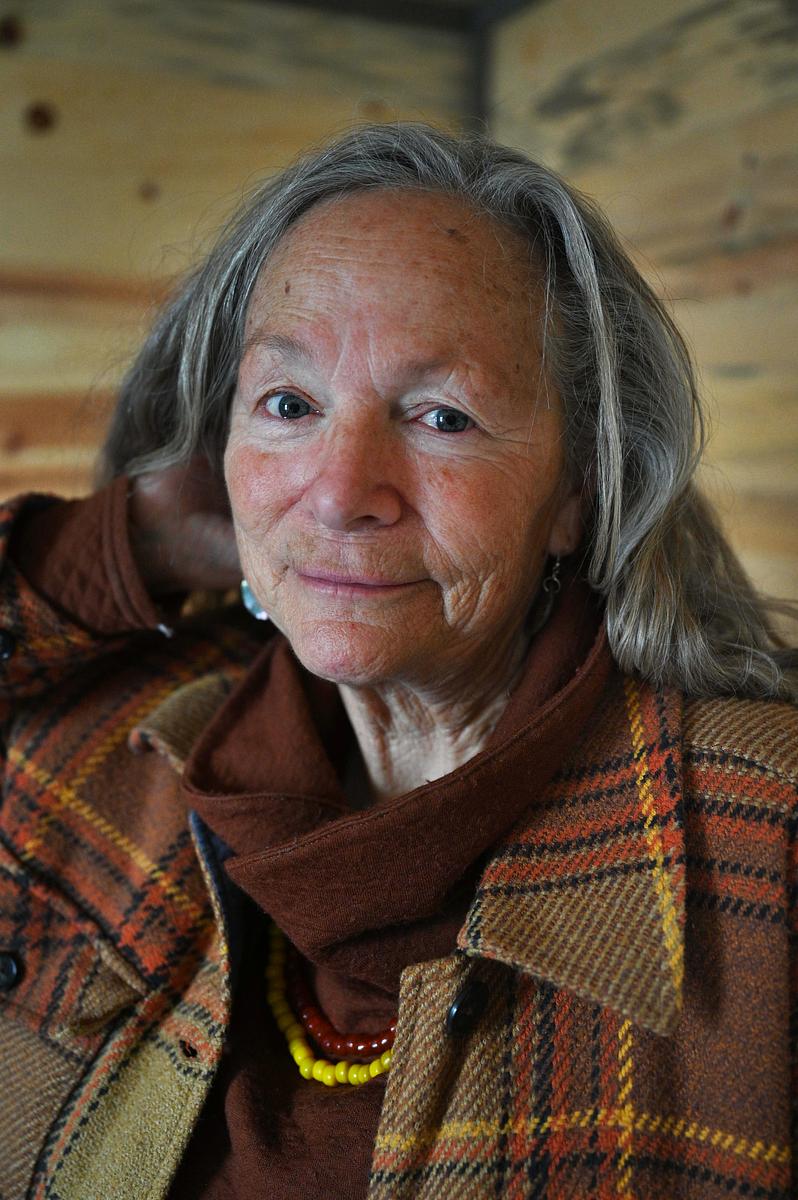

“Think of the starvation,” said Kim Paul, executive director of Piikani Lodge Health Institute, a nonprofit on the Blackfeet Reservation that promotes health and well-being. “Think of the annihilation. Think of the genocide. Think of the damn boarding schools.”From the early 1800s to the 1970s, the U.S. government separated Native children — including Wyatt’s great-grandfathers and grandmothers — from their families and forced them to attend Christian boarding schools, where they were physically, sexually and emotionally abused, and often died. Tribes experienced widespread language and culture loss as a result. And survivors have said their experiences at boarding school made it hard for them to parent, discipline their children and show love.

Entrenched systemic inequities coupled with everyday racism, Paul added, can send a message, particularly to young people, that “we’re not equal to everyone else.”

“There’s this constant oppression of you’re not good enough, you’re not good enough,” she said. “It just becomes this really intense generational hopelessness, and I think that that’s the driving factor [behind suicide] here.”

Inadequate health care may be another contributing factor, experts say. Indian Health Service, the federal entity responsible for providing health care to federally recognized tribes nationwide, is chronically underfunded. Budget shortfalls mean the agency struggles to recruit and retain medical professionals. Patients often face long wait times for care and see a revolving door of providers.

“There’s just so many fronts when it comes to suicide.”

Terrance LaFromboise, Blackfeet Tribal Behavioral Health

When people can’t get timely and quality mental health care, tribal health experts say, they may self-medicate with alcohol or try to cope in other unhealthy ways. A 2016 report found that one in four Browning eighth graders indicated they binge drank in the past two weeks, and 42% of Browning High School students reported that a family member had severe drug or alcohol problems. It’s well documented that alcohol misuse increases a person’s suicide risk, as substance abuse is associated with increased impulsivity, social isolation and aggressive behavior. Living in rural areas, like the Blackfeet Reservation, also increases a person’s risk for suicide.

Those overlapping, complex and deep-rooted factors make the high rate of suicide on the Blackfeet Reservation a difficult crisis to address, said Terrance Lafromboise, who works at Blackfeet Tribal Behavioral Health and previously worked with the state on its suicide prevention program.

“I would always say, ‘We could focus on youth,’” he said. “We could do that work, but then we’re going to miss something over here. Then we’re over here, and we’re shifting [away from youth] and working, and guess what? The youth over there are going to struggle. There’s so just many fronts when it comes to suicide.”

One thing the Mad Plume sisters are convinced of — and health experts agree — is that solutions must emerge from their own community. A 2022 review of 56 academic reports and other information, including Indigenous texts, songs, videos and reports, found that when it comes to the disproportionately high rates of Indigenous suicide in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States, “conventional Western approaches to suicide prevention by themselves have largely failed.” At the same time, initiatives that incorporated community engagement and Indigenous cultures “have been shown to have substantial impact on suicide-related outcomes.” Another study, published by the American Journal of Public Health, found that “serious gaps between the assumptions and practices of typical prevention programming and Indigenous understandings of suicide stand in the way of effective interventions.”

“We’re being underfunded and we’re being told how we heal. That clearly doesn’t work.”

Lynn Mad Plume

The research confirms what Lynn has seen firsthand.

“We’re being underfunded and we’re being told how we heal,” she said. “That clearly doesn’t work. We need mental health resources and support for our communities so that we can build it. That takes us stepping up and coming together.”

CULTURE AND CARE

The Mad Plumes’ program is among the latest examples in Montana of homegrown mental health services that incorporate elements of Native cultures in an attempt to establish new systems of support for people who are suffering.

Apsáalooke Healing, an outpatient treatment center in Crow Agency, hosts sweat lodge ceremonies for people recovering from addiction. Rocky Boy Health Center in Box Elder holds summer sobriety camps where participants smudge and bead. Blackfeet Tribal Behavioral Health in Browning emphasizes cultural belonging by issuing certificates of achievement in the Blackfoot language and hosting transition ceremonies for people who graduate from certain programs. Clinical Director Durand Bear Medicine keeps a smudge box and sweetgrass in his office. Cultural practices, he said, directly supported his own addiction recovery. Now he shares that support with others.

“Teaching individuals that these are the resources that are for free, that are in your community, you have access to them at any given point, and there are healing processes, should you want to use them, it can help” he said. “And I always tell them that I am a product of that.”

“It’s not an idea that culture saves us. It’s a truth.”

Kim Paul, executive director, Piikani Lodge Health Institute

Kim Paul, whose Blackfoot name is Long Time Charging Woman, has personally felt the strength of culture. When she began to learn her language, she said, she felt empowered and gained a new understanding of her identity.

“I became human,” she said.

“It’s not an idea that culture saves us,” she added. “It’s a truth.”

In Two Medicine, where the Mad Plumes keep most of their horses, reminders of Wyatt are everywhere. His blue house, inherited from his grandmother, is on the property, and his orange-and-brown Ford truck is in the driveway. One of his favorite horses, Jetson, has become, as Lynn puts it, “a therapy all-star.” And Wyatt’s grave — decorated with athletic medals, orange flowers, toy cars, beef jerky and hot sauce — rests on a hill overlooking the spot where his family now hosts youth camps to help others process the kinds of grief that proved too much for Wyatt to bear.

They know they can’t prevent every suicide on the reservation. But they hope to reach kids, like Wyatt, who struggle to recognize and respect their emotions, who can be overwhelmed by hardship, and for whom traditional therapy may not be the most effective fit.

“I know Wyatt’s OK,” Lynn said. “But I’m still really mad about it. I’m still really upset about it. Because he should be here. But this wouldn’t have happened without Wyatt.”

This story was supported in part by a grant from The Carter Center. Montana Free Press is part of the Mental Health Parity Collaborative, a group of newsrooms covering stories about mental health care access and inequities in the United State. Partners on this project include The Carter Center and newsrooms in select states across the country.