LIVINGSTON — Montana has long been an energy exporter, with Powder River Basin coal and Missouri River hydroelectric dams helping keep the lights on across Washington and Oregon.

But as those states increasingly turn to renewable energy sources, Montana will have to overhaul the way it produces energy if it wants to remain a supplier.

What’s currently lacking is a way for Montana’s grid to smooth the power-generation peaks and lulls that are part and parcel of wind and solar energy production. Peak demand for energy doesn’t always line up with when the sun shines and the wind blows, so some form of electricity storage is necessary to make renewable energy reliable.

The Gordon Butte Pumped Hydro Project is designed to provide that storage. The $1 billion facility in rural Meagher County is ready to begin construction in 2020.

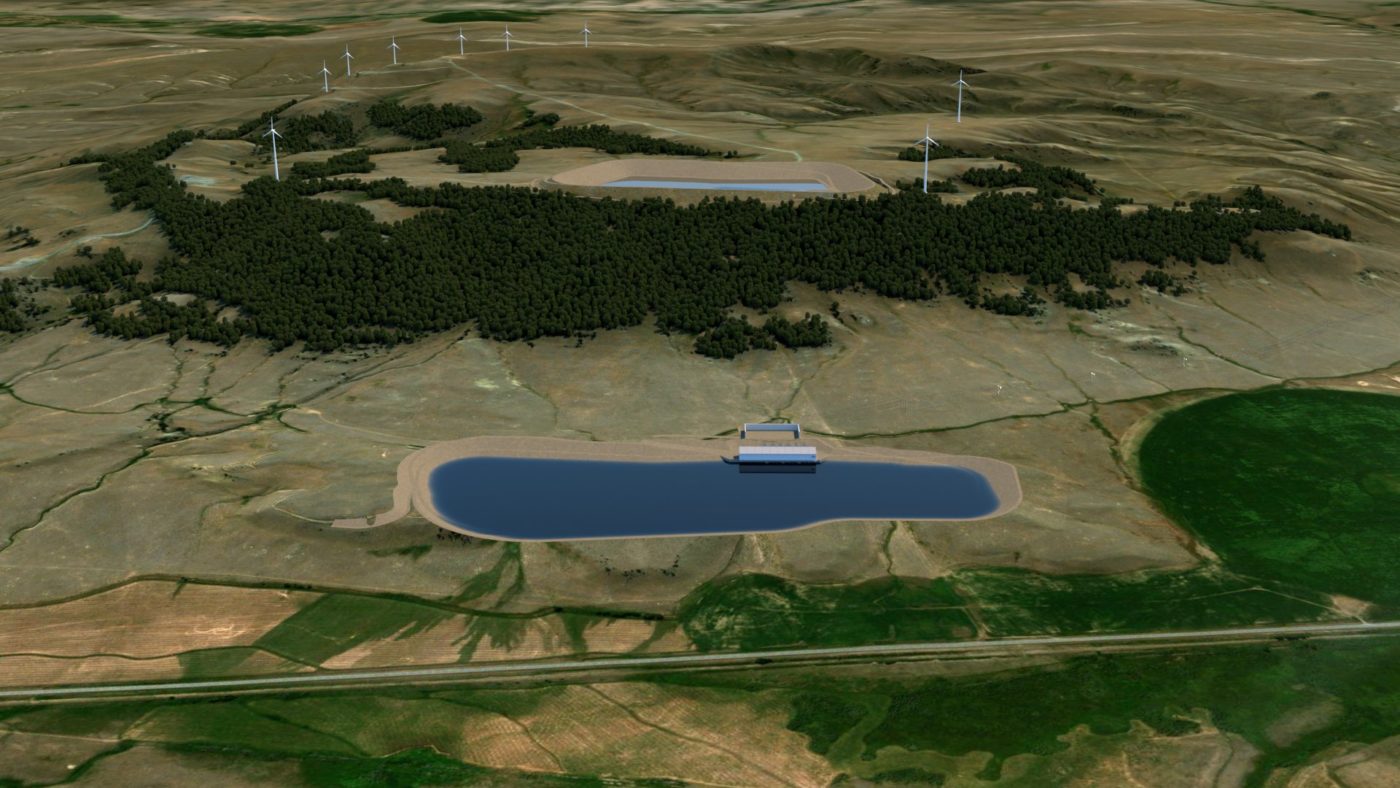

The facility will be essentially a mechanical battery that works by purchasing excess electricity when supply exceeds demand — generally when electricity is cheapest — and using that power to pump water into a reservoir to be built on top of Gordon Butte, south of Martinsdale. When demand exceeds supply, the water would be released through turbines into a lower reservoir, generating electricity. The plant is designed to produce 400 MW.

“This could single-handedly ensure Montana remains an energy powerhouse as we transition off of coal.”

For comparison, Colstrip Units 1 and 2, which are scheduled to close later this year, have a combined capacity of 614 MW.

Bozeman-based Absaroka Energy originally proposed the project in 2010 and has been aggressively developing it since 2013. The process so far has involved finding a site (the company says it holds an option to purchase), acquiring water rights, navigating the federal permitting process, and securing financing from Denmark’s Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners.

Such hurdles make launching a pumped storage project “like finding a spotted, multicolor unicorn,” Absaroka CEO Carl Borgquist said.

With financing in place and permits in hand, two questions remain: where will the facility get the electricity to operate the facility, and who will buy the energy it produces?

Borgquist said those conversations are ongoing. No utility company has yet committed to the project.

In the meantime, the renewable energy sector has high hopes for Gordon Butte.

“This could single-handedly ensure Montana remains an energy powerhouse as we transition off of coal,” said Jeff Fox, Montana policy manager for Renewable Northwest, a Portland-based nonprofit organization that advocates renewable energy development. Montana exports half of the electricity it produces each year, according to the Energy Information Administration. The majority of that exported energy has historically been produced by burning coal.

But Montana’s energy customers — about half of the state’s electricity production is exported to Washington and Oregon — are shifting away from fossil fuels. Washington has pledged to phase out coal-sourced energy by 2025, and to have 100 percent of its electricity generated by renewable sources by 2045. Oregon has set a goal of 50 percent renewable energy by 2050.

“That is Montana’s future energy customers waving a big flag saying, ‘We want clean energy,’” said Brian Fadie, clean energy program director for the Montana Environmental Information Center.

But wind power has been slow to take off in Montana. According to the American Wind Energy Association, every state bordering Montana has more developed wind energy capacity. Solar and wind account for just 10.6 percent of Montana’s electricity production.

Much of the lack of progress with renewables has to do with transmission issues, Fadie said. The power lines by which Montana exports electricity are mostly full. That will change at the end of 2019, when two of the four units at the coal-fired power plant in Colstrip are scheduled to go off-line, freeing up significant transmission capacity, Fadie said.

But in order to meet customer demand, Montana energy producers will have to provide renewable energy during times of peak demand — evenings, for example, when people are at home, cooking dinner, watching TV, and otherwise using electricity, which isn’t necessarily when renewable resources are generating. Gordon Butte is designed to create stores of renewable supply to meet those demands.

According to the Department of Energy, there are 50 pumped storage hydropower plants operational or in development in the U.S., with a collective operative capacity of 21 GW, and 325 operational pumped storage hydro plants worldwide. Gordon Butte would be the first in Montana.

Pumped storage — a technology that has been in use in the U.S. since the 1920s — currently accounts for more than 95% of worldwide energy storage capacity.

Even so, according to a 2016 DOE report, pumped hydro storage projects have been slow to develop because the technology is undervalued in the marketplace, and incentives are scarce. With many utility companies having monopolies on electricity sales, pumped hydro storage projects can take years to get off the ground, Fox said.

For example, NorthWestern Energy, which provides electricity to Montana customers, has a financial incentive to own its own generating facilities, Fadie said.

Bleau LaFave, director of long term resources for NorthWestern, said the company has examined the potential of adding pumped storage capacity to its energy portfolio. LaFave said the company thinks the technology is valuable for the flexibility it can provide, but is limited in that it can operate for only a certain amount of time before it has to be recharged.

Gordon Butte is designed to take 8.5 hours to fully empty and 10 hours to recharge.

LaFave offered the example of a three-day cold snap earlier this year when NorthWestern had to buy electricity on the open market to supply customer demand. Pumped storage, LaFave said, wouldn’t solve such long-term demand spikes.

Borgquist acknowledged that pumped hydro storage projects are designed not to fulfill long-term demand, but to provide consistency during short-term fluctuations.

Montana continues to have significant fossil fuel reserves that may be difficult to monetize in the transition to renewable energy. The state has one-third of the recoverable coal reserves in the United States, and significant natural gas and oil deposits, according to the Energy Information Administration.

But the state also possesses untapped potential in renewable energy. A 2016 report by the Northwest Power and Conservation Council found that Montana’s wind potential is likely higher than that of Washington state’s Columbia Gorge. As of 2016, Montana had just 700 MW of developed capacity, compared to the gorge’s 5,700 MW.

Borgquist said that as Washington and Oregon’s renewable energy deadlines approach, he anticipates a need for about a dozen pumped hydro storage projects across the West. Absaroka is working on another pumped hydro storage project in Wyoming.

Meagher County Commission Chairman Ben Hurwitz said the Gordon Butte project represents a host of benefits for the local community. The facility would require 300 employees during its four-year construction, and likely a few dozen during its operation, which could extend for a century, Borgquist said.

Accordingly, Hurwitz said, the project enjoys a rare level of public approval.

“I haven’t heard anyone express any bad feeling about it,” Hurwitz said. Plus, “It’ll be a helluva tax base.”

But the project’s benefits have the potential to extend beyond Meagher County, and beyond Montana.

“It’ll play a truly regional role and help the Western grid at large,” Fox said.