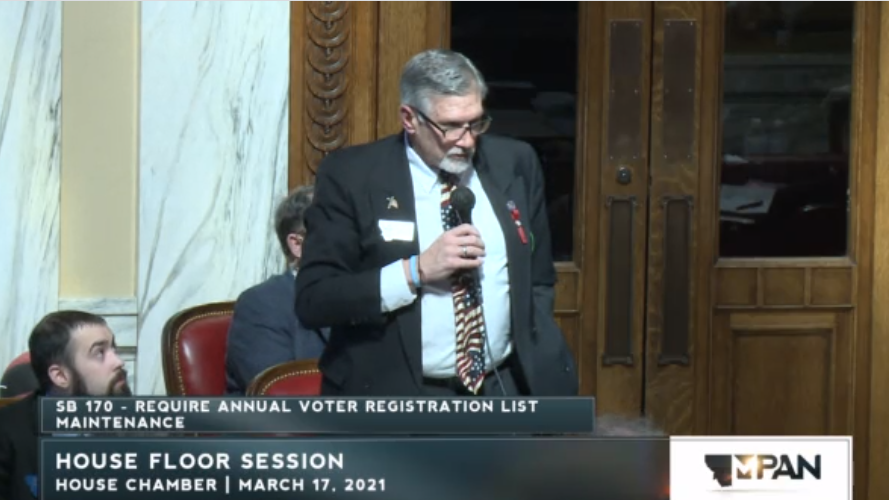

On March 17, Rep. Brad Tschida, R-Missoula, slid his microphone from its cradle and addressed the House floor in the concerned tone that’s become familiar to anyone following the Legislature’s deliberations on election law changes. Tschida and his colleagues were well into a debate on Senate Bill 170, which would require county election officials to update voter rolls every year. And as he has numerous times this session, Tschida dove straight into a polite demand to protect “our most sacred activity,” voting.

The word “fraud” gets thrown around a lot in the context of elections, Tschida said, as does the assertion that there is no evidence of fraud — an assertion, he added, that he finds “highly suspect.” But his testimony took an uncharacteristically cryptic turn from there. Without giving too much away, he said, an assessment had been conducted of all the mail-in ballots in Missoula County from the 2020 general election.

“Let’s just say that there weren’t a lot of zeros after the decimal point of the number of ballots that had an issue with them,” Tschida continued. “And in the next week or two, there will be some information coming out that verifies that information. So when we say there’s no fraudulent activities or activities of wrongdoing, in two weeks you’re going to have a much clearer picture of how easy that is to allow to take place. So this [SB 170] is absolutely necessary.”

SB 170 ultimately passed the House on a largely party-line vote, landing on the governor’s desk this week. As for the Missoula County information Tschida alluded to, that manifested March 24 in the form of a post on the website Real Clear Investigations by John R. Lott Jr., an economist, longtime gun-rights advocate and former U.S. Department of Justice adviser appointed by President Donald Trump, who moved to Missoula last summer. Lott wrote that a “recent audit” of Missoula’s mail-in ballots had uncovered “irregularities” that could have swung the local results.

Legally speaking, the process Lott referred to was not an audit, according to Missoula attorney Quentin Rhoades. Rhoades told Montana Free Press that he prefers to call it a “review and count” of the affirmation envelopes in which Missoula voters enclosed their 2020 mail-in ballots. For the past six months, Rhoades has been representing, pro bono, a group of Missoula citizens, including Tschida, who requested access to a trove of information from the Missoula County Elections Office. Tschida did not respond to emails and phone messages requesting an interview.

The story stretches back to early last fall, when Rhoades began having informal conversations with former Missoula City Council member Lyn Hellegaard and others about monitoring the upcoming election for abnormalities. The group approached Tschida as well, and on Oct. 30, Rhoades submitted a records request on Tschida’s behalf to Missoula County Election Administrator Bradley Seaman asking for access to information about altered ballots and the signed ballot envelopes.

After roughly two months of discussion and additional records requests, Seaman and several members of his staff transported the sealed boxes containing the requested envelopes to a rented space at the Missoula County Fairgrounds. Rhoades met them there with 20 volunteers, including Hellegaard and Tschida, and over the span of five hours the volunteers hand-counted every affirmation envelope Seaman’s office could legally provide. (Seaman told MTFP roughly a dozen envelopes were not included to protect the privacy of legally protected confidential voters). The volunteers kept track of their counts on blank spreadsheets furnished by Seaman, and county employees unsealed and resealed each box between counting to maintain the legal chain of custody.

“What they’re claiming is a failure to do the policies and procedures laid out that we have clear documentation on. And it is an insult to the election workers, staff in this office and the Secretary of State’s office that certified this result.”

Missoula County Election Administrator Bradley Seaman

“I gathered up all of the count sheets from everybody that was in the room,” Hellegaard told MTFP. “I then took them home, ran an adding machine tape on them when I got done with that, totaled it up, then compared that to the number that our Secretary of State’s office had published on the number of ballots, or votes, that had been cast in Missoula County.”

Hellegaard’s results are fueling no small amount of tension in Missoula. Her tally from the volunteers’ count of affirmation envelopes totaled 67,899. The Secretary of State’s office recorded 72,491 votes in Missoula County. Lott subsequently promoted the group’s allegation of a 4,592-vote discrepancy in the county’s 2020 general election results — an error of nearly 7%, and enough votes to have potentially altered the outcome in more than a dozen legislative races.

The Missoula County Commission fired back in a Missoula Current op-ed this week, calling the claims “baseless” and stating that the citizen group “failed to implement any sort of verification process” for its count. The allegation not only undermines public faith in the integrity of the democratic process, the commission wrote, but undermines the hard work done by elections staff both in Missoula and at the Secretary of State’s office.

Seaman told MTFP that a discrepancy of that size could not have escaped the rigor of current election procedure. Each envelope contains a barcode that’s scanned into the state’s voter database, he said, which is how voters are able to see whether their ballot has been received on the state’s MyVoter webpage. The envelope is then inspected for signature verification, and is later compared to a report generated by the voter database. Three precincts are randomly selected for a post-election audit involving a physical count of ballots, and a post-election canvass is conducted by the county auditor and county commissioners to account for all ballots. The results are then certified by the Secretary of State.

“What they’re claiming is a failure to do the policies and procedures laid out that we have clear documentation on,” Seaman said. “And it is an insult to the election workers, staff in this office and the Secretary of State’s office that certified this result.”

Hellegaard declined to speculate on how a discrepancy could have occurred or been overlooked at the county or state level. Her group presented an issue, she said, and now it’s up to election officials to provide an explanation. She disputes the county’s position that the error lies in the citizen group’s count.

“You know, counting envelopes, we’re not talking rocket science here,” Hellegaard said.

“We’re hoping we can go to the Legislature and get our laws shored up so that people are confident that their votes actually count the way they want them to.”

Former Missoula City Council member Lyn Hellegaard

Rhoades said that, from a legal standpoint, the citizen count would be admissible as evidence in court. Other assertions made by the group, and included in Lott’s post, such as one citizen counter’s claim of similarities in a number of voter signatures, would require input from a specialist to reach that bar. Rhoades, who repeatedly emphasized that Seaman and his staff have been cooperative and accommodating throughout the process, ventured a number of guesses as to what could have led to the group’s alleged discrepancy. He said it could be as simple as the elections office having misplaced several boxes of envelopes.

Seaman said that’s highly unlikely, since his staff had to prepare those boxes and remove all confidential voter envelopes prior to transporting them to the fairgrounds. The transportation itself, he added, was overseen by two judges.

The dispute is likely to continue. Rhoades, Hellegaard and Secretary of State Communications Director Richie Meley confirm that members of the group are meeting with the Secretary of State’s office April 6 to present their findings. But each side is placing responsibility for resolving the alleged discrepancy squarely in the other’s court. Seaman said he has encouraged the group to conduct another count or investigate further. Hellegaard said she is unwilling to commit to that, since they had to raise $3,000 to pay for the records request the first time. Hellegaard, Rhoades and Seaman all confirmed that a portion of that money was refunded since Seaman had initially scheduled the group for two full days of access to the records.

Hellegaard believes it’s up to the county to find an answer and suggested it have a disinterested third party conduct an audit. For now, that appears improbable. Instead, Seaman said, his office would welcome litigation on the issue, which he is confident would prove in court that there’s no merit to the allegations. Rhoades said that given Seaman’s consistent cooperation and the group’s unencumbered ability to review all the documents legally available so far, there’s currently nothing to file a lawsuit about.

What is clear is that the dust kicked up in Missoula has already crossed the Continental Divide to the state Capitol, as evidenced by Tschida’s veiled mention of the situation last month. In that regard, Hellegaard has already accomplished one of her stated goals in watchdogging Missoula’s 2020 election.

“We’re hoping we can go to the Legislature and get our laws shored up so that people are confident that their votes actually count the way they want them to,” Hellegaard told MTFP Friday.

Seaman finds those policy implications particularly concerning. That, he said, is the real issue.

“Whatever misinformation is used as factual evidence to make a change to the state laws or to promote widespread allegations of voter fraud, there needs to be some sort of response to this,” he said.

latest stories

What Montana’s U.S. House candidates are saying about the southern border

Even though the U.S.-Mexico border is 1,000 miles south of Montana, congressional candidates have made it a central issue in this year’s election. Here’s what they said when we asked them what they’d like to change.

The GOP-heavy primary for Montana’s utility-regulating PSC

Lawmakers, former commissioners and engineers are heavily represented in the June 4 primary election for the Public Service Commission, which has been heavily red for two decades. Here’s how the candidates are differentiating themselves.

Medicaid unwinding deals a blow to a tenuous system of care for Native Americans

About a year into the process of redetermining Medicaid eligibility after the COVID-19 public health emergency, more than 20 million people nationwide have been kicked off the joint federal-state program for low-income families. Native Americans are proving particularly vulnerable to losing coverage and face greater obstacles to re-enrolling in Medicaid or finding other coverage.