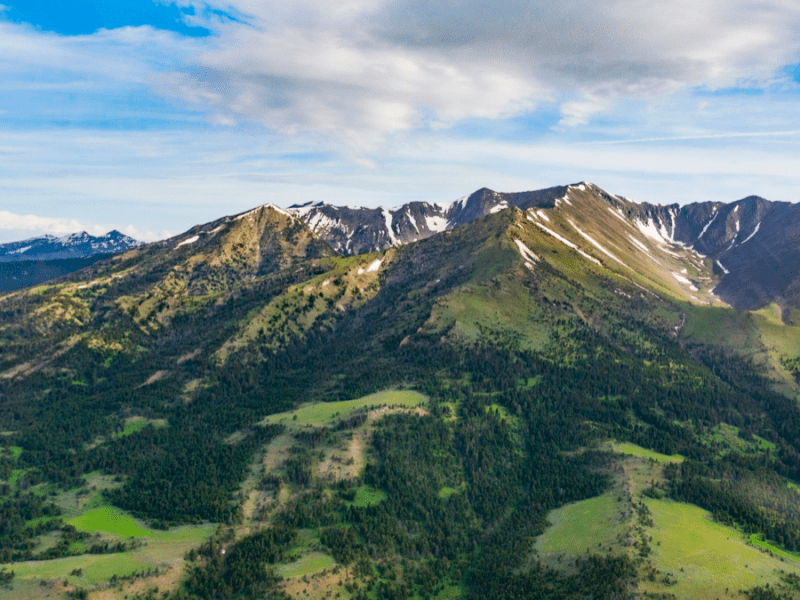

An island range patterned with checkerboard land ownership, the Crazy Mountains are the backdrop to one of the most “vexing” land-use debates in the state. Crow Indians, the Northern Pacific Railroad, the U.S. Forest Service, ranchers, recreationists and politicians have all claimed ownership in parts of the Crazy Mountains at various times, seeding more than a century of access and land-use disputes that continue today. Between an active lawsuit, two land-swap proposals winding through Forest Service administrative channels, and pending development of some of the largest private properties in the foothills of the Crazies, the future of one of the state’s most iconic and disputed landscapes is playing out now. Today we publish Part II of a three-part series exploring the past, present and future of Montana’s Crazy Mountains.

On a brisk fall day in 2016, Bozeman resident Rob Gregoire received a trespassing ticket while hunting on a trail that’s appeared on maps of the Crazy Mountains for at least 80 years. The Hailstone Ranch, which owns part or all of seven square-mile sections of checkerboard land on the east side of the Crazies, had posted signs saying the Forest Service doesn’t have an easement across its land, so Gregoire knew public access to East Trunk Trail was disputed. But after consulting with Alex Sienkiewicz, the district ranger on that part of Custer Gallatin National Forest, Gregoire was assured he had a right to hike the trail.

As it wound through the grasslands interspersed with pine trees, the trail became faint in places, so Gregoire used an app on his phone to guide him. But when he returned to the trailhead after his outing on Nov. 23, 2016, he found a Sweet Grass County sheriff’s deputy waiting to issue him a $500 ticket, plus court fees. Gregoire decided to fight the citation and raised more than $8,000 to cover his attorney fees. Two months after the ticket was issued, Gregoire told the Billings Gazette, “I guess I’m the test case” to determine whether the Forest Service has a historical easement across sections of private land owned by Hailstone Ranch.

read part I

Whose Crazies are they?

How the Crazy Mountains became ground zero in Montana’s most vexing land-use debate.

The merit of the trespassing ticket was never decided by the court, and determining whether a historical easement exists would have required another lawsuit — one Gregoire didn’t have the funding or appetite to pursue. “After talking with a lot of lawyers, we learned that, OK, even if I [won on the trespassing claim], it wouldn’t prevent the sheriff from giving the next guy a ticket,” Gregoire told Montana Free Press. In June 2017, he decided to accept a deferred prosecution. As part of Gregoire’s agreement with the Sweet Grass County attorney, he donated $500 to the Sweet Grass Community Foundation and agreed to stay off Hailstone Ranch’s property for a year.

Gregoire had some money left over from his fundraising campaign to fight the citation, so he divvied it up between a number of nonprofit groups representing environmental, hunting and access interests. Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, which advocates for access to public land, was one. Park County Environmental Council, which is active on environmental issues in the Livingston area, was another.

Fast forward four years. Gregoire is now a member of the Crazy Mountain Access Project, which includes about a dozen Montanans representing various interests — landowners, conservationists, hunters — who are developing a land swap proposal to resolve disputes over public access along the mountain range’s eastern flank.

As with most things related to the Crazy Mountains, the proposal, the process and the underlying politics are complex. The Crazy Mountain Access Project’s proposal includes several components, but the crux of it consolidates several sections of checkerboard land by swapping 5,200 acres of generally higher-elevation private property for 3,600 acres of lower-elevation Forest Service land and building a new 22-mile trail between Sweet Grass and Big Timber canyons traversing almost entirely Forest Service property. Like a Rubik’s cube starting to come together, the swap would group several square-mile sections of Forest Service land inked green on agency maps and similarly consolidate the paler private sections.

related

Sale of Crazy Mountain Ranch finalized

Crazy Mountain Ranch has been purchased by Lone Mountain Land Company, a subsidiary of CrossHarbor Capital Partners, which owns the Yellowstone Club near Big Sky.

But the proposal is far from anodyne. Two groups that received some of the leftover funds from Gregoire’s short-lived challenge to the trespassing ticket are at odds over the exchange and the process that generated it. The Park County Environmental Council says the Crazy Mountain Access Project has engaged in a collaborative, trust-building effort that will establish stronger protections for public land and avoid litigation between neighbors. Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, which is involved in a lawsuit asking the Forest Service to protect four historical trails in the Crazies, says landowners have the upper hand and the Crazy Mountain Access Project has excluded members of the public who stand to lose access to prime elk habitat in the foothills of the Crazies.

THE CASE FOR THE EAST SIDE SWAP

Park County Environmental Council deputy director and Crazy Mountain Access Project member Erica Lighthiser says it hasn’t been that long since other mountain ranges in Montana suffered from the administrative and legal headache presented by checkerboard ownership. “I think about the Gallatins and the Bridgers — at one time, those two ranges were just as bad as the Crazies,” she said. “You can resolve so many issues if you can consolidate some of the land. … Maybe we can get there in the Crazies.”

Lighthiser likes the certainty she finds in the proposal, commonly called the East Side Land Swap. “With all that private land within the forest boundary, that land is vulnerable,” she said. “The people who own it now may be wonderful stewards of the land, but it’s uncertain what the future holds.” Lighthiser acknowledges that the proposal isn’t perfect — “and it’s not going to be perfect,” she said — but she appreciates that it’s brought together people who tend to be pretty siloed in their interests. “When you sit down and talk, you find that you have a lot more in common than not. Our kids go to school together, we see each other in the grocery store,” she said.

Just assembling the Crazy Mountain Access Project to work through some potential solutions has been complicated and controversial. Several Crazy Mountain Access Project members are also part of another group working on issues in the area, the Crazy Mountain Working Group, which was organized by a handful of large landowners in the Crazies in 2017. A year and a half ago, the Yellowstone Club, an exclusive ski resort and residential community near Big Sky for the well-heeled — think Bill Gates, Ben Affleck, Tom Brady — became involved in land swap proposals in the area and the Crazy Mountain Access Project was born. The Yellowstone Club’s involvement raised plenty of eyebrows in Park and Sweet Grass counties, but the club is no stranger to land swaps. In the 1990s, a number of complicated land exchanges between the Forest Service and timber baron-turned-real estate magnate Tim Blixseth consolidated some of the land that later became the Yellowstone Club.

Custer Gallatin Forest Supervisor Mary Erickson, who’s currently on a 3.5-month detail with the Forest Service’s national office, said that for several years the Yellowstone Club has been eyeing a land exchange on a different part of the forest to expand its expert skiing terrain. Recognizing that its swap wasn’t a top priority for the Forest Service, the Yellowstone Club offered to contribute resources to another access issue to help bring the 500-acre exchange it sought to fruition. Now, despite the fact that the Yellowstone Club is more than 70 miles as the crow flies from the Crazies, it’s paying for two land exchange consultants to coordinate the efforts of the Crazy Mountain Access Project, and it will cover the construction cost of the new 22-mile East Trunk Trail if it’s approved by the Forest Service.

Lighthiser said the consultants have brought expertise to the conversation and helped the proposal take a more formal shape.

“I think about the Gallatins and the Bridgers — at one time, those two ranges were just as bad as the Crazies. You can resolve so many issues if you can consolidate some of the land.”

Crazy Mountain Access Project member Erica Lighthiser

“This is not something you can figure out over a cup of coffee at the bar in Big Timber,” she said. “It involves five landowners. It’s a pretty complicated deal.”

Another component of the proposal involves Crazy Peak, which is owned by the Switchback Ranch. Crazy Peak is an important part of the spiritual landscape for Crow Indians, and access to it would allow them to fast and pray there in the tradition of Chief Plenty Coups. Switchback Ranch owner and Yellowstone Club member David Leuschen has agreed to give Crow tribal members access to Crazy Peak if the swap goes through.

In addition to being complicated, technical undertakings that often require years of conversation, land swaps by their nature tend to involve both controversy and compromise. John Salazar, a Livingston-based Crazy Mountain Access Project member who is on the board of the Montana Wildlife Federation, said an ideal outcome would mean “everyone knows they got something, but they know they didn’t get everything.” A handful of sportsmen and access groups say the East Side Land Swap doesn’t meet that threshold, that the proposal is weighted too heavily in landowners’ favor.

THE CASE AGAINST THE SWAP

Since the East Side Land Swap hasn’t officially entered the Forest Service’s administrative purview and undergone all the study and public comment that process entails, it’s hard to gauge the level of public support for the swap, but it has undoubtedly garnered some vocal opponents.

In a letter published in the Missoula Current last August, several groups, including the Montana chapter of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, Enhancing Montana’s Wildlife and Habitat, Skyline Sportsmen and Friends of the Crazy Mountains, outlined their issues with both the proposal and the process.

“The current proposal would establish one public access funnel on the entire east side of the Crazies. It should not be supported by public landowners who value their rights to access their own land unhindered, free of charge and without intimidation,” the letter reads. “The only party that should support this is the private landowners who stand to gain some of the best elk habitat in the state and exclusive access to our public lands and resources.”

Concerns about the privatization of wildlife in the Crazy Mountains go back decades. As far back as the 1940s, there have been reports of landowners on the east side blocking public access during hunting season. Today, an outfitted elk hunt in the Crazies can cost $1,000 or more per day. Limited public access has also resulted in a situation where elk numbers are consistently higher than wildlife managers want them to be — the hunting public just can’t get to them.

“It’s a direct line between lack of access and growing elk [numbers],” said former Fish and Wildlife Commissioner and Livingston resident Dan Vermillion.

Erickson said the Forest Service participates in Crazy Mountain Working Group meetings as an invited guest and has been tracking developments in the East Side Swap proposed by the Crazy Mountain Access Project, but the agency hasn’t indicated a position on the proposal. There will be lots to evaluate once a more formal proposal is in place, she said.

Lighthiser said she expects the Crazy Mountain Access Project will have something formal to submit to the Forest Service by the end of the year.

THE SOUTH SIDE LAND SWAP

Land exchange advocates hope that the Forest Service’s recent approval of a smaller land swap on the south side of the Crazies will create a certain level of momentum for the East Side Land Swap. Earlier this month, the Forest Service announced that it’s moving forward with a land swap involving about 1,900 acres and two ranches along the southern edge of the range.

“Land exchanges, by their very nature, are always controversial. In general, people might appreciate the lands that might come into [public ownership], but they don’t really want to see anything come out of public ownership.”

Custer Gallatin Forest Supervisor Mary Erickson

The proposal the Forest Service put before the public last fall included swaps involving three landowners, but the agency has decided not to move forward with an exchange involving some property owned by the Crazy Mountain Ranch. Known locally as the Marlboro Ranch, the 18,000-acre property was purchased by tobacco giant Philip Morris Inc. in 2000 as a place for cigarette smokers loyal to the Marlboro brand to enjoy an all-inclusive dude ranch reminiscent of the Old West.

The Forest Service decided not to move forward with the Crazy Mountain Ranch exchange in response to public input, but said that given more time and consideration, it might pursue it in the future. Gregoire said that portion of the swap was unpopular and inequitable due in part to the low recreational value of the land the Forest Service stood to gain and the fact that the public already has an easement to access to some of that land. Others said the remote location of the two Crazy Mountain Ranch parcels proposed for the swap was thought to be less vulnerable to development and thus a lower priority for protection.

Forest Service discussions regarding the Crazy Mountain Ranch property go back at least 14 years, predating Erickson’s tenure with the Custer Gallatin National Forest. She said she’s not surprised that the proposal elicited strong opinions.

“Land exchanges, by their very nature, are always controversial,” she said. “In general, people might appreciate the lands that might come into [public ownership], but they don’t really want to see anything come out of public ownership.”

The other swaps, involving one section of the Wild Eagle Mountain Ranch and two sections owned by the Rock Creek Ranch, enjoy broader public support. As part of the deal, the Forest Service will obtain a recorded easement for a 100-foot section of Robinson Bench Road that currently lacks one, and both ranches have agreed to put the Forest Service sections they acquire under conservation easements.

The conservation easements play into the Montana Wilderness Association’s support for the South Side Swap — and also help explain why it has reservations about the East Side Swap. In an email to MTFP, MWA Conservation Director Emily Cleveland said her organization hasn’t taken an official position on the East Side Swap, but that there are several things that could make it stronger from a conservation perspective. MWA wants the sections traded into private ownership to be put under conservation easements, particularly those along Sweet Grass Creek. They’d also like assurance that the swap doesn’t relinquish public interest in active access disputes, including trails currently being litigated. Finally, MWA would like the Crow Tribe or the Forest Service to have first right of refusal on any private lands that come up for sale within the forest boundary.

Cleveland said MWA generally supports efforts to consolidate land in the Crazies, since checkerboard land makes it more difficult to establish protective designations like wilderness or backcountry management areas.

Gregoire also supports consolidation efforts. “Unless you want to corner-hop, take your chances there, all that stuff is locked up,” he said. These days he finds himself spending more time in areas with contiguous public access and more straightforward land ownership patterns. He’s hunting and hiking in the Madison, Gravelly and Gallatin ranges.

“Because of the access, I don’t go into the Crazies as much as I do other areas,” he said.

This story was updated May 22 to clarify that the Crazy Mountain Working Group and the Crazy Mountain Access Project are different groups with different scopes of interest and involvement.

read part III

The Crazy Mountains’ next act

With a heliskiing operation looking for a foothold and the rumored sale of one of the largest ranches in the range, Montanans are wondering what’s next for this isolated and iconic landscape.

latest stories

Republican lawmakers mount three separate pushes for special sessions

A trio of special session requests from Republican lawmakers each touch on election-year issues, but lawmakers have historically had little success calling themselves into a special session.

What Montana’s candidates for governor have to say about renewing Medicaid expansion

We asked Republican, Democratic and Libertarian candidates if they would support reauthorizing the low-income health care program, which has in the past been the subject of vigorous debates in the Capitol — and is up for renewal again next year. Here’s what they had to say.

‘I hope I can be an example to others:’ Carroll to celebrate Indigenous graduate

During spring commencement, Jaydee Weatherwax — a member of the Blackfeet Tribe from Browning — will become one of the first Native Americans to earn a master’s degree in social work from Carroll College in Helena.