On March 22, 1972, all 100 delegates to the Montana Constitutional Convention gathered at the Capitol in Helena to sign off on a new state Constitution they’d just spent months researching, debating, negotiating and writing — and which would be ratified by voters on June 6 of that year. In observance of the 50th anniversary of the delegates’ adoption of the document, Montana Free Press this week presents a series of articles exploring the state Constitution’s history, legacy, influence and future. Today: The impetus and implementation of Indian Education for All.

Article X, Section 1, Part 2: The state recognizes the distinct and unique cultural heritage of the American Indians and is committed in its educational goals to the preservation of their cultural integrity.

On Jan. 31, 1972, two students from the Fort Peck Indian Reservation appeared in Helena with a request that, however brief, helped to fuel a lasting shift in Montana’s public education system. Standing before the Constitutional Convention’s Bill of Rights Committee, Mavis Scott and Diana Lueppe asked delegates to make classroom instruction relevant and sensitive to the state’s Native peoples.

“We would like, very simply, our history, our culture, our identity,” Scott said.

Nearly six weeks later, convention delegate Dorothy Eck referenced their testimony when introducing a constitutional amendment committing Montana to the recognition and preservation of Indigenous heritage. Though the phrase “Indian Education for All” wouldn’t officially enter the state’s lexicon for another 27 years, the ensuing discussion made it clear that the request wasn’t just about teaching tribal culture to tribal students. Delegate Richard Champoux, a history and political science professor at Flathead Valley Community College in Kalispell, likened the proposal to standard lessons on English or French history and to a particular celebration of Irish culture — St. Patrick’s Day — popular in, among other places, Butte.

“All of us are proud of our heritage, whether we be English, Irish, Jewish, or whatever,” Champoux told his fellow delegates. “We are proud because we know about our history, our culture and our integrity — our heritage. Are we now to continue to deny this to these, the first citizens of the State of Montana?”

Other delegates elaborated on that sentiment, including a Presbyterian minister from Poplar, a cattleman from Kirby and an attorney whose clients included the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. In all, 14 delegates spoke in favor of Eck’s amendment, and only one proposed a change. Gene Harbaugh, the Poplar minister, recommended adding “in its educational goals” to the amendment’s language to more strongly tie it to the Constitution’s guarantee of equal educational opportunity.

The discussion not only addressed the appeal Scott and Lueppe had entered into the record, but transformed Article X into the Constitution’s primary vehicle for Native American interests. Harbaugh openly maligned the treatment that Montana’s tribes had received at the convention, saying tribal representatives were “getting the runaround” from delegates shuffling their requests from one committee to another. He wasn’t alone in his assessment.

“This has been a cop-out, and they know it,” Champoux said. “What we’ve been doing, then, is pushing them back and forth between the committees in an attempt to get rid of them, and they know it.”

There were no Native Americans among the convention’s 100 elected delegates.

Harbaugh’s addition, and the amendment as a whole, passed with 89 delegates voting in favor and one opposing. Speaking with the Associated Press after the vote, Earl Barlow, a Blackfeet member who played an instrumental role in organizing Native testimony, called it “the dawn of a new era of understanding of our people and our culture, which is vital to our existence.”

Sharen Kickingwoman, Indigenous justice program manager at the ACLU of Montana, attributes that success largely to the groundswell of activism among Native Americans in the 1970s. The nation as a whole was shifting toward more Indigenous self-determination, she said. Tribal colleges were popping up around the country. Responding to pressure from tribal communities reeling from the widespread practice of forced adoptions, Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act in 1978. The discussion at Montana’s Constitutional Convention about Indigenous peoples’ role and representation in public education, Kickingwoman said, was a reflection of those grassroots forces.

“To have those conversations was a really powerful moment that was spurred by young people and really showed their power,” she said.

While the Constitution’s ratification officially enshrined Indigenous heritage as part of the state’s educational mission, realizing that promise in Montana classrooms proved much more challenging. In the years immediately after the convention, the Legislature directed the Board of Public Education and Board of Regents to create culturally relevant programs and develop strategies for training teachers in Indian studies. Lawmakers also passed a bill in 1973 requiring all teachers working on or near reservations to take courses on Indian studies, but revised the requirement in 1979 to make it optional.

One of the most significant post-convention developments came in 1984, when the Board of Public Education established the Montana Advisory Council on Indian Education, a collection of tribal representatives and education leaders charged with helping the board and the Office of Public Instruction make good on public education’s constitutional mandate.

Much of this early history is mapped out in a 2011 article in the Montana Law Review penned by Carol Juneau and her daughter, Denise Juneau, both of whom played pivotal and distinct roles in strengthening Indian Education for All. In an interview with Montana Free Press, Denise Juneau characterized the implementation of the provision in the 1970s and ’80s as a series of “starts and stops,” with the earliest efforts primarily driven by tribal members keen on incorporating tribal perspectives and Indigenous languages in schools. Without funding from the state, Juneau said, the promise to recognize Indian heritage in K-12 instruction was “just sort of this lofty language” in the state Constitution.

related

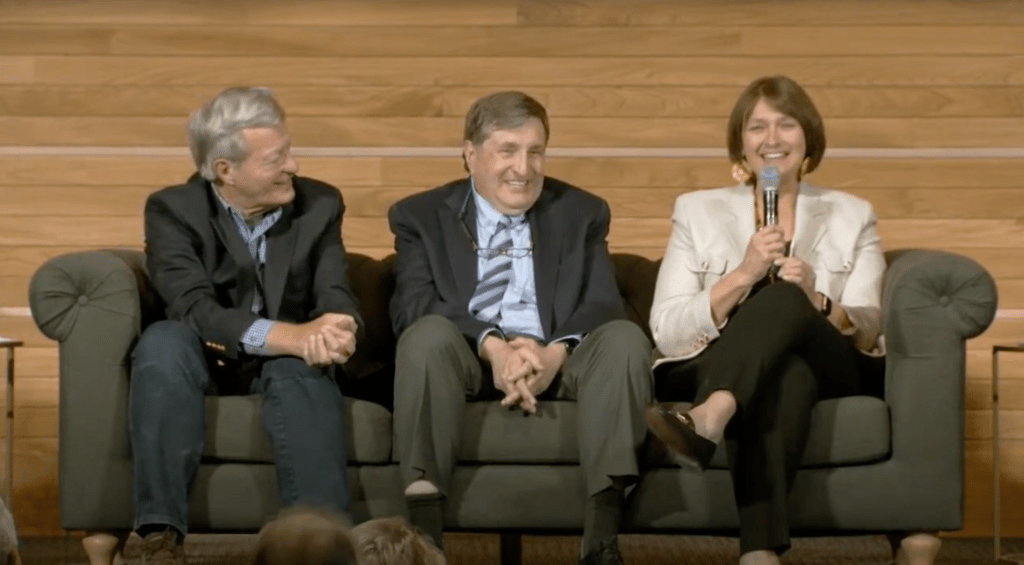

Bob Campbell’s constitutional legacy

Tributes poured in Wednesday for Bob Campbell, who as a delegate to the 1972 Montana Constitutional Convention wrote the document’s provisions for the right to privacy and the right to a clean and healthful environment. Campbell died Tuesday night in Missoula. He was 81 and died of natural causes after suffering from dementia.

The Montana Constitution, up close and personal

When 100 delegates gathered in 1972 to create a new Constitution for Montana, reporter Chuck Johnson had a front-row seat to history in the making. Here’s his recollection of that Montana milestone — and what it’s meant for the state in the half-century since — in Chuck’s own words.

How the Montana Constitution shapes the state’s environmental landscape

Legal scholars, environmental activists and practicing attorneys say a handful of forward-looking provisions in the Montana Constitution drafted by delegates 50 years ago have secured some of the strongest environmental protections and most progressive stream access laws in the country. Cases decided by the Montana Supreme Court in 1984, 1999, 2011 and 2014 have been particularly pivotal in fleshing out what Montanans’ right to a “clean and healthful environment” means in practice.

Fifty years later, is Montana’s ‘Right To Know’ working?

In debating and drafting the new version of Montana’s constitution, delegates tried to fill a serious gap that existed before. Situated within Article 2, Section 9, there now exists a tool to guard against government opacity.

“There was no way to really influence or even incentivize or do anything like that,” Juneau recalled. “These were all volunteers, trying to do their best to get Native content in the classrooms, and there was really no accountability from schools to make sure that that was happening.”

Lack of funding ultimately led to a lawsuit in 1985, and a ruling from the Montana Supreme Court that the state’s K-12 education budget was not equitable. That decision did little to move the funding needle, however, and implementation of Indian Education for All continued to fall largely on individual educators and localized initiatives. Juneau remembered that as a public school teacher in Browning in the 1990s, she would weed through textbooks for culturally relevant material, or supplement curricula with Native author James Welch’s novel “Fools Crow” and field trips to the site of the Marias Massacre, where her students would hear directly from Blackfeet elders.

“Teachers had to really be intentional about first learning for themselves the content that they needed to teach, and then supplementing the content that was at the school level,” Juneau said.

In 1999, Indian Education for All finally appeared to gain traction — and an official moniker — with the Legislature’s passage of an eponymously titled law. The bill was sponsored by Carol Juneau, a member of North Dakota’s Mandan and Hidatsa tribes and the first president of Blackfeet Community College in Browning, and outlined a clear path for incorporating Indian Education for All into the state’s curricular and accreditation standards. Even so, lawmakers continued to leave the effort unfunded, culminating in a landmark lawsuit by the Montana Quality Education Coalition in 2004. A year later, the Legislature revised its definition of “quality education” to include Indigenous heritage and appropriated $4.3 million to the Office of Public Instruction to provide the necessary curricula, training and grants.

Denise Juneau was one of the first employees to join OPI’s new Indian Education for All division, eventually going on to head the division before serving two terms as state Superintendent of Public Instruction. She sees that first chunk of state funding as critical in finally giving Indian Education for All its institutional legs.

“OPI created over 300 lesson plans in about a year, pushed out tons of publications, worked with tribes on tribal histories,” Juneau said. “It just became a very much more content-rich environment for teachers to grab onto, to learn for themselves and then to implement into the classes.”

On July 22, 2021, the ACLU of Montana and the nonprofit Native American Rights Fund filed a class action lawsuit accusing the state of failing to meet its constitutional obligations in Indian education. The complaint, lodged on behalf of 18 individuals and five tribal nations, claims that OPI and other state education offices have not done enough to develop and enforce adequate content standards or to work cooperatively with tribal entities to implement Indian Education for All. ACLU attorney Alex Rate said that unlike previous litigation focused on state funding, the current lawsuit centers on “oversight and implementation.”

“They’re not seeing Indian education robustly incorporated into public school curricula,” Rate said of the plaintiffs. “What you see instead is a sort of lip service paid to Native American Heritage Month or some instruction around Thanksgiving or things like that that really don’t accord with the very broad mandate that’s contained in the Constitution.”

In response, Attorney General Austin Knudsen filed a request in October that the case be dismissed, alleging that the plaintiffs had failed to show any actual injury. Knudsen further argued that the local control afforded to school districts in Montana’s public education system means it’s up to those districts, not state officials, to ensure Indian Education for All is implemented.

“The Legislature has given the [Superintendent of Public Instruction] limited enumerated powers and duties for the supervision of schools,” Knudsen’s filing read. “She does not possess general compliance authority over all education matters and lacks the power to withhold or impact IEFA funding.”

The case is still in its early stages in Cascade County District Court, where a judge has yet to rule on the state’s motion to dismiss. But the lawsuit, filed just shy of the constitution’s 50th anniversary, underscores the ongoing challenges to making Indian Education for All a reality.

Even as they applaud the progress made so far, Indian Education for All advocates recognize that Indigenous heritage is far from a guaranteed presence in every Montana classroom. And while the Montana University System has taken steps in the past decade to better reflect Indigenous culture on state campuses and offer more diverse courses on Indian history and languages, critics have accused higher education of moving slowly on the issue as well.

Though Knudsen refutes OPI’s oversight responsibilities on the legal stage, the agency has continued to develop instructional materials, model curricula and professional development webinars for teachers focused on Indian education. Among the moves by Superintendent Elsie Arntzen lauded by OPI is the separation of the agency’s Indian Education for All staff into its own distinct unit.

According to joint written responses from unit Director Zack Hawkins and Indian Education Specialist Mike Jetty, OPI also introduced new social studies standards last year that include Indian Education for All at all grade levels. The two noted that OPI’s future goals include continuing to host an annual Indian Education for All Best Practices Conference for educators, working with college campuses to raise awareness of Indian education in their teacher preparation programs, and immersing K-12 students in Indian language preservation.

For Kickingwoman, the importance of exposing Native and non-Native students alike to Indigenous culture can’t be overstated. She’s a member of the Blackfeet and Gros Ventre tribes who grew up in Missoula, and said it wasn’t until college that she had a Native teacher. Being the only Native student in her K-12 classrooms was “an isolating experience,” she continued, and she found that a lack of understanding among her non-Native peers about nearby tribal cultures often resulted in their reliance on inaccurate stereotypes.

“Having that knowledge, especially localized as to what’s happening, founded in truth, I think will build a lot of bridges,” Kickingwoman said.

Denise Juneau doesn’t have to think long for an example of what Indian Education for All can and, in some places, does look like at the classroom level. She recalled hearing from a Missoula teacher who invited a Salish educator to visit with her students. The presenter displayed some cultural items and played a drum song, which, Juneau said, roused the attention of a Blackfeet student who’d had trouble engaging in class.

“The next day, this kid showed up in class with the drum and sang Honor Song, and basically after that was sort of engaged in the classroom because he had seen himself present in the classroom setting,” Juneau continued. “That is a powerful story about seeing yourself and seeing your culture represented.”

latest stories

Attorney General Knudsen accused of soliciting ghost competitor for campaign finance purposes

Incumbent Attorney General Austin Knudsen and his opponent in the GOP primary face political practices complaints following reports that Knudsen acknowledged recruiting an opponent so he could accept larger donations.

Why Gianforte’s reelection bid has drawn a challenge from the right

Greg Gianforte is stumping as a pragmatic conservative in an election year dominated by culture war issues. That’s helped earn him a challenge from the GOP’s right flank.

Addiction treatment homes say funding fixes don’t go far enough

Montana health officials have started a voucher system to help people with substance use disorders move into transitional housing as they rebuild their lives. But those who run the clinical houses said the new money isn’t enough to fix a financial hole after a prior state revamp.